LXXX

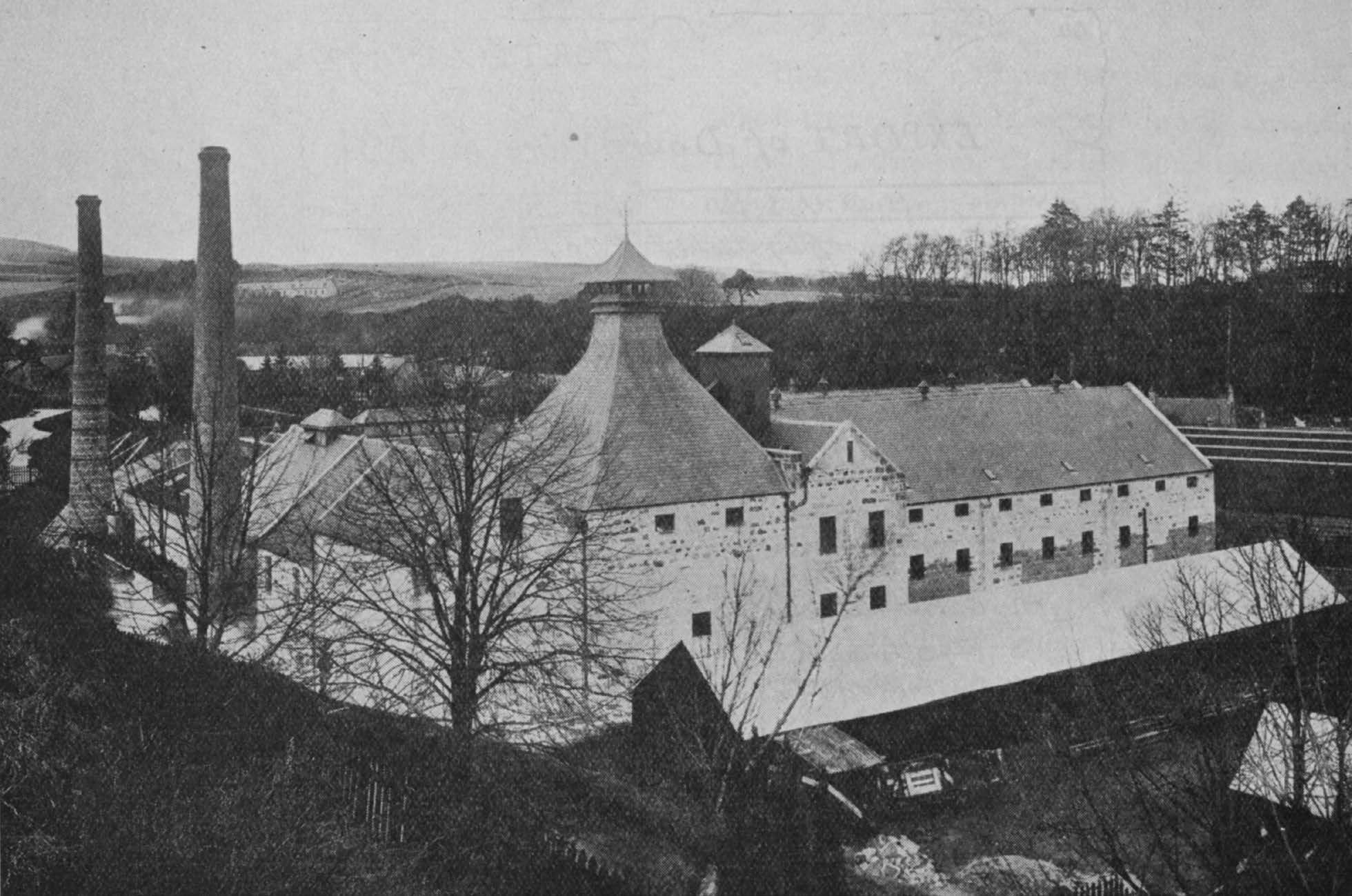

Glen-Spey Distillery, Rothes, Morayshire.

May 14th, 1925

Speyside, as all the world knows, is the home of most of the famous Highland distilleries, and quite apart from the character or virtues of the various Whiskies, some of these establishments have distinct “personalities” of their own which almost unconsciously impress a visitor. Such a distillery is Messrs. Gilbey’s “Glen-Spey,” situated at the southern entrance to the town of Rothes in the midst of grand mountain and river scenery on the fringe of that great Whisky county – Morayshire. Any attempt to explain the subtle attraction of “Glen-Spey” (again we are not referring to the Whisky – excellent as it is!) would be superfluous in a practical article, but the place has an indefinably pleasant atmosphere, and a visit is an experience worth repeating.

There are two dominant features in the working of Glen-Spey Distillery. One is the ultra-efficient arrangement of the buildings, machinery and apparatus, linking up the various processes in one harmonious system. The second outstanding factor is the dazzling cleanliness of the whole establishment. Three years ago all the buildings, excepting the still-house and tun-room, were completely destroyed by fire, and in erecting new premises the firm had the advantage of being able to plan them on the most up-to-date lines, and so avoid the congestion noticeable in some older distilleries where additions have been constantly made.

The maltings consist of a handsome stone building, and this department has been so organised as to eradicate manual labour entirely, apart from the single operation of turning the grain during germination on the malting floors. Barley is brought from Rothes station in wagons and tipped into a hopper on the ground floor of the maltings. This hopper is capable of holding as much as thirty quarters at a time, and from it the barley passes by elevator to a cleaning machine, and subsequently to a band conveyor for distribution on the floor of the lofts, or removal to three steeps, which usually contain forty quarters each. To feed the steeps a reserve supply of spring water is maintained in a large tank adjacent to these vessels. After steeping, the barley is conveyed in the customary fashion to the malting floors to undergo the process of germination. When ready for drying, the malt is taken by a screw conveyor to an elevator communicating with the kiln. For prevention of fire, the kiln door is covered with sheet-iron. The kiln-floor is of wire, with accommodation for fifty quarters, and a King’s patent turning machine has been installed with results said to be extremely beneficial. Another labour-saving device, due to the inventive capacity of the brewer, affords rapid communication between the maltings and the engine-room, and enables the maltmen to apply power to the kiln turner, elevators, or any section of the conveyor system without consulting the engineer. When power is required in the maltings a small bell connected with the engine-room is rung, and the engineer responds by immediately starting up the main engine. Levers governing the main shaft are ingeniously arranged on each floor of the maltings, so that merely by pulling the nearest lever the maltman can transfer the driving power to any required part of the machinery.

The furnace at Glen-Spey Distillery is controlled by a King’s patent regulator, and the fuel consists of a mixture of coke and peat, the latter in a proportion of about one-third. Grinding is performed by a large mill manufactured by Messrs. Dey, of Huntly, dealing with more than 230 bushels per hour; the weighing machine was supplied from the Birmingham works of Messrs. Avery; and two extensive storage hoppers complete the outfit of a most interesting malting department.

Passing into the mash-house adjoining the mill-room, one discovers a handsomely-painted building that can truthfully be described as a model of its kind. It is scrupulously clean, spacious and well ventilated, with all the usual appliances – mash-tun, mashing-machine, sparge rod, and so on – obviously in first-class condition. Above the mash-tun are four grist hoppers, each with accommodation for 230 bushels, and two capacious hot-water tanks heated by steam. One thousand bushels of malt are mashed every week, and the resultant draff is removed from the base of the tun by a drag which carries it out of the building to two wagons. After cartage to Rothes station, the wet draff is taken by rail to dairy farmers in the neighbourhood of Aberdeen.

Following the mashing process, the wort is drained into an underback, and afterwards raised to a receiver by means of a plunger pump. The wort receiver and refrigerator occupy a separate little apartment near the tun-room. In the long well-lit tun-room there are six wash-backs with switching apparatus, and an unobtrusive but powerful donkey-engine which raises yeast to the tun-room, drives the switchers, pumps, feints and Spirits, and rotates the “rummagers” in the wash-still. Power for other purposes is supplied by a Tangye steam engine.

In extent, good ventilation, and lighting, the still-house is typical of the other buildings at Glen-Spey Distillery. There are two well-burnished stills for wash and low-Wines respectively – the former of 3,280 gallons’ capacity, and the latter capable of containing 2,800 gallons. Both stills are furnace-heated. At the far end of the still-house is a receiver room which might easily be mistaken for an exhibition display. The vessels are neatly arranged, and every piece of copper is polished to perfection. Cleanliness is desirable in a distillery of all places, and it is an undoubted and important fact that in establishments such as Glen-Spey, where managers carry on a perpetual crusade against dirt, employees take a noticeable pride in their work.

A unique feature of the receiver room is the separate vessel for feints. The general practice is, of course, to use one receiver for low-Wines and feints, and the exception in this case is due to the fact that when the low-Wine still reaches a temperature of 90 degrees the feints are separately pumped back into the wash charger.

The Whisky is described as “Glen-Spey Glenlivet,” and the normal weekly output is 2,500 gallons stored in duty-free warehouses with accommodation for 7,500 casks.

For conveying effluent to the central purification plant at Rothes, Glen-Spey, Glen-Rothes and Glen-Grant distilleries use a joint pipe through which the burnt Ale and spent lees pass by gravity; and the fourth distillery, Speyburn, has a private pipe, owing to its relatively isolated position, a mile from the town. The purification plant is jointly owned by the distilleries on the same principle as the draff-drying plant in Campbeltown.

A brief description of the process may be of interest. Arriving at the purification works, the effluent flows into a number of large receiving vessels, and thence into five huge evaporating tubes. Evaporation is performed by steam from two large boilers, and the process continues until a “syrupy” substance has been produced. This substance is then heated in ovens until it becomes caked, two auxiliary furnaces being employed for heating purposes. From the ovens the cake passes through a “crusher,” and finally through a mill, so that it forms a powder well-suited for fertilising. The powder is sold to farmers under the name of “Maltassa.” Chemical analysis shows that it contains 11 per cent. of phosphate of lime, 7 per cent. of sulphate of potash, and 6 per cent. of ammonia, and its fertilising powers have been praised in numerous testimonials. Twelve tons of “Maltassa” are produced each week, but despite the fair market for the product, the expense of maintaining the purification plant greatly prejudices the commercial value of this enterprise. Purification is, indeed, regarded as a “necessary evil” in most of the Speyside distilleries.

Images © The British Library Board